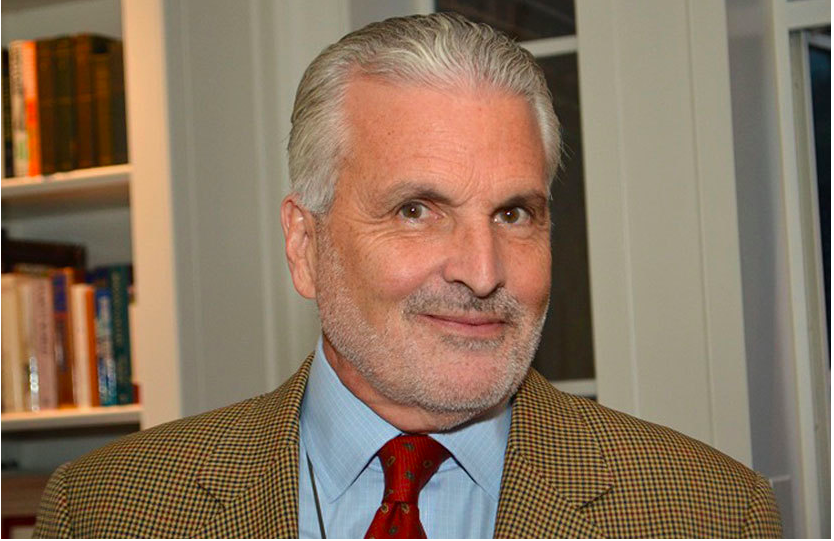

We mourn the loss of our dear friend, J.D. McClatchy

Sandy has been a beloved member of our family since the article he published in the NY Times on the 100th anniversary of Thornton Wilder's birth. We share it with you here.

Wilder and the Marvels of the Heart By J. D. MCCLATCHY APRIL 13, 1997 From The New York Times

A friend of mine, now a distinguished author and scholar, remembers that as a teen-ager in California she would wander in the stacks of the Berkeley Public Library. One day, with a random curiosity, she picked a novel off the shelf and turned to the opening paragraph. ''The earth sighed as it turned in its course; the shadow of night crept gradually along the Mediterranean, and Asia was left in darkness. The great cliff that would one day be called Gibraltar held for a long time a gleam of red and orange . . . at the mouth of the Nile the water lay like a wet pavement.'' She was enthralled. She decided right there to become a writer, and hoped sometime, somehow to write sentences as ravishing as these. The novel was ''The Woman of Andros,'' by Thornton Wilder.

Others have had a similar experience with Wilder's books. Mine came later than my friend's, and therefore less dramatically, but the pleasure was as profound and as enduring. Next Thursday, April 17, marks the hundredth anniversary of Wilder's birth. The customary tributes are planned: a commemorative stamp is being issued, a Web site established, a Modern Library reader published. But the celebrations, I suspect, will be scattered and modest. Wilder's star, so bright on either side of World War II, has dimmed. For many readers nowadays, his name carries the faint whiff of the sachet, and his best work will seem sentimental and sententious to those who prefer their books braced with raw passions or caustic ironies.

His best-known work remains ''Our Town,'' which was first performed in 1938 and has ever since been by far the most often produced American play. When Raymond Massey took it on tour to American G.I.'s in Europe in 1945, soon after the fighting had stopped, he reported that tears streamed down the faces of hardened soldiers. (They still stream down mine.) What undoubtedly touched those soldiers is the play's plangent nostalgia, the ache for home, for home's rootedness and security. But Wilder's portrait of the citizens of Grover's Corners, their lives and deaths, is not about the past so much as it is about the way we remember the past, what is illuminated and obscured by memory, gained and lost, the pathos of innocence, the sublimity of the ordinary, the acceptance of the dark ineluctable. And it is about what Wilder called ''the eternal part'' of us all. The religious reader will sense something more in that phrase. But Wilder himself would have called it the mind -- an impulse, a characteristic, a power that sets us apart and onward.

To speak in such terms nowadays risks the sophisticate's smirk. Wilder stitched on homespun, and the result sometimes resembled the motto on a sampler. The instinct to generalize shouldn't be confused with softness. Wilder was no sentimentalist -- a type, in his own definition, ''whose desire that things be happy exceeds his desire and suppressed knowledge that things be truthful; he demands that he be lied to. He secretly knows that it is a lie; hence his emptiness, his elations and his heartlessness.'' Like Wilde or Chekhov or Shaw, he was essentially a moralist. Each of these playwrights could dramatize ideas and conduct, could make us think about our feelings. They sought, in their different ways, to clarify life by portraying its contradictions. Wilder took the given and raised it to the higher power of reflection. And he did it the hard way: by telling the truth.

Wilder was a complex man. There are the plays and the novels, for which he was awarded three Pulitzer Prizes. But there is a great deal more. He had a profound respect for tradition and thought that literature ''more resembled a torch race than a furious dispute among heirs.'' He was an erudite scholar of James Joyce and Lope de Vega, and lectured at both Harvard and the University of Chicago. He served in both world wars. He played the piano well enough to tackle the Beethoven sonatas, and wrote an opera libretto. He wrote screenplays for George Cukor, Alfred Hitchcock and Vittorio De Sica. He translated ''A Doll's House'' and ''Waiting for Godot.'' His published journals shimmer. He had a dizzyingly wide circle of friendships and counted among his acquaintances Gertrude Stein, Montgomery Clift, Coco Chanel, Sigmund Freud, Henry Luce, Alexander Woollcott, Laurence Olivier, Dorothy Parker, Jean-Paul Sartre, Tallulah Bankhead, Gene Tunney, Max Beerbohm, Felix Frankfurter, Ernest Hemingway and Sibyl Colefax.

He looked, Tyrone Guthrie said, like a piano tuner, owned only one suit at a time and spoke in a fidgety, accelerating, inexhaustible manner. He left all his domestic and business affairs for a devoted sister (his de facto ''wife'') to handle. He drank and smoked too much, was gregarious and self-effacing. He loathed self-pity. His compassion was clear-eyed and his generosities practical. He was endlessly obliging. Sylvia Beach said tartly that he reminded her of a man taking everyone in the world on a Sunday school picnic and trying to get them all on the bus at the same time. He especially liked helping old friends and talented beginners. He encouraged, for instance, a young actor named Orson Welles; and when the young Edward Albee was a fellow guest at Yaddo and busy writing poems, he remembers Wilder suggesting to him, ''Why don't you try writing plays?'' He was never without a new enthusiasm; even into his 70's, he was boning up on advances in microbiology, studying Greek vase painting or the theories of Claude Levi-Strauss.

Wilder seems to have been a repressed homosexual, baffled by his own desires and ashamed of his furtive attempts to act on them, and yet he made family life the arena of his imagination and wrote about it with a rare and compassionate understanding. Perhaps for this reason too, he cultivated the company of older, intelligent women as confidantes, hostesses, muses. He was a compulsive traveler and socializer, simultaneously to savor and to protect against a deep loneliness. His identical twin had died at birth, and there was a side to Wilder that was always restlessly searching to allay an unsatisfiable need. He had no ''sturdy last resource against the occasional conviction 'I don't belong.' ''

Myself, I prefer his novels to his plays. They haven't the accumulated glamour of those by Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Faulkner already in the pantheon. But the best of them remain remarkable accomplishments and deserve a wider audience. His first, ''The Cabala'' (1926), involves an Innocent Abroad, and is filled with worldly shrewdness and lapidary wit. It was an astonishing feat for a 29-year-old tyro, and won him instant acclaim. A year later he published ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey.'' With ''The Woman of Andros'' (1930) and ''The Ides of March'' (1948), Wilder upended the heavy social realism that dominated books of the day, and gave the exotic historical novel a genuine philosophical poise. But his two best novels have American settings. ''Heaven's My Destination'' (1935) is a picaresque comedy about the adventures of an itinerant textbook salesman, the earnest, self-righteous, Bible-thumping George Brush. ''The Eighth Day'' (1967) is a remarkable hybrid, part murder mystery, part family saga. Its hero, a mining engineer named John Ashley, is another of Wilder's unsettling anatomies of the fabled American innocence. Americans, he once said, are people who have outgrown their fathers. Like Whitman's, Wilder's Americans are solitary, energetic, inventive, restless but disciplined, responsible but detached. They are one with the cold moonlight that falls equally on corpse and cradle, apple and ocean.

''I am not interested,'' he told an interviewer, ''in the ephemeral -- such subjects as the adulteries of dentists. I am interested in those things that repeat and repeat and repeat in the lives of the millions.'' He meant, of course, the mysteries and marvels of the heart. Wilder once described Tolstoy as ''a great eye, above the roof, above the town, above the planet, from which nothing was hid.'' Wilder too looked on our life, steadily, never blinking at its pain and incongruities. But he was not a tortured artist or an embittered one. Instead, he was a master of high comedy. Into sorrows and convictions he mixed humor. In the ordinary he found what is wondrous strange. The tone of high comedy, he confided to his journal, is ''lyrical, diaphanous and tender.'' If one added to those qualities a rueful joy and a deep humanity, then Wilder could be said to belong to a special group of artists -- Jane Austen, Ivan Turgenev, Jean Renoir and Elizabeth Bishop are among them -- whose work refreshes our intelligence. The older I get, and the more often I reread Wilder's novels, the brighter they seem, more subtle and courageous, filled with new surprises and earned wisdom.

J. D. McClatchy