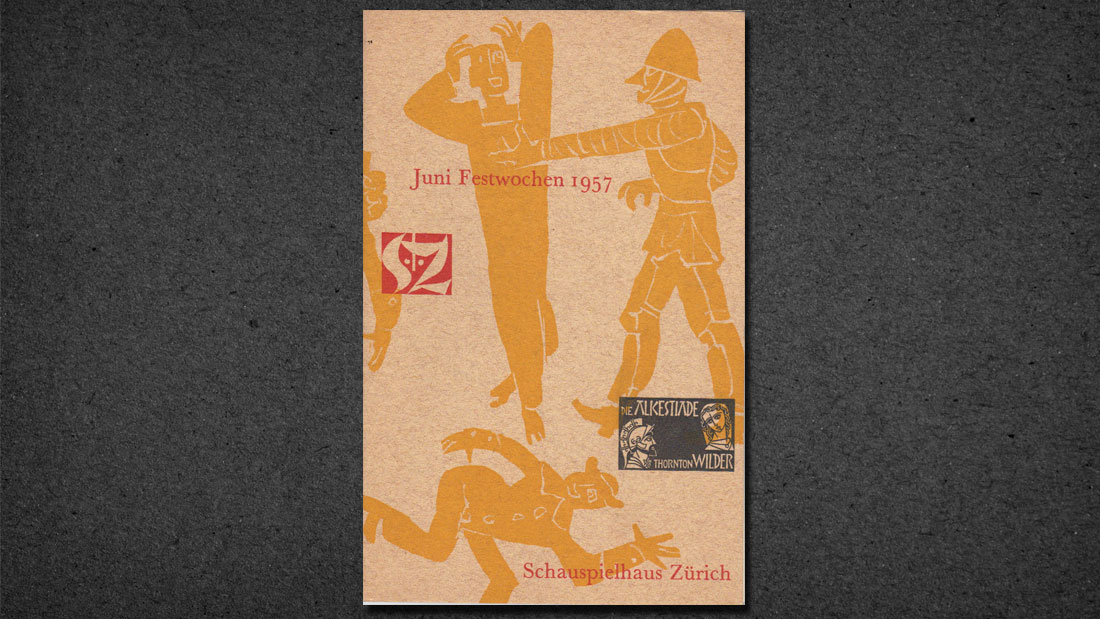

The Alcestiad

NOTES ON THE ALCESTIAD

BY THORNTON WILDER

Alcestis chose to die for her husband. We are often told that soldiers die for their country, that reformers and men of science lay down their lives for us. Who commands them? Whence, and how do they receive the command?

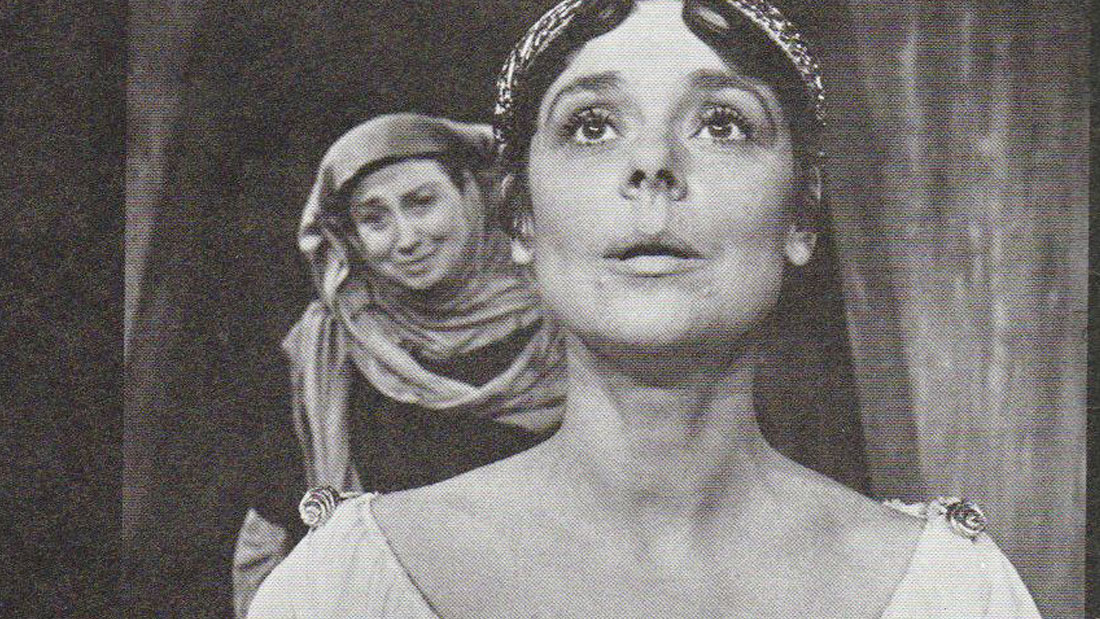

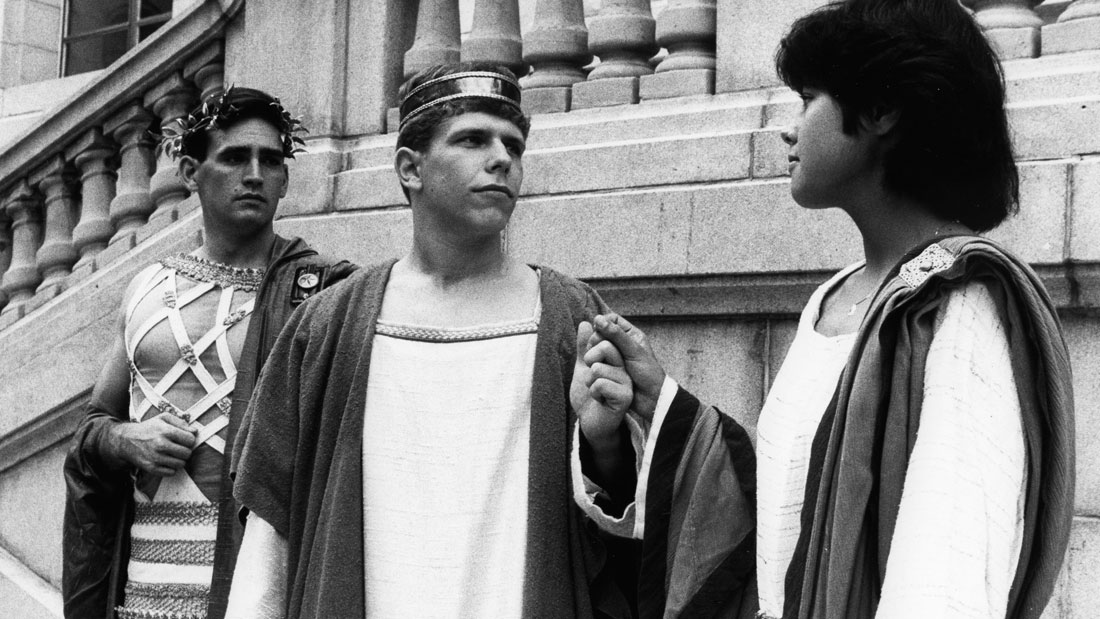

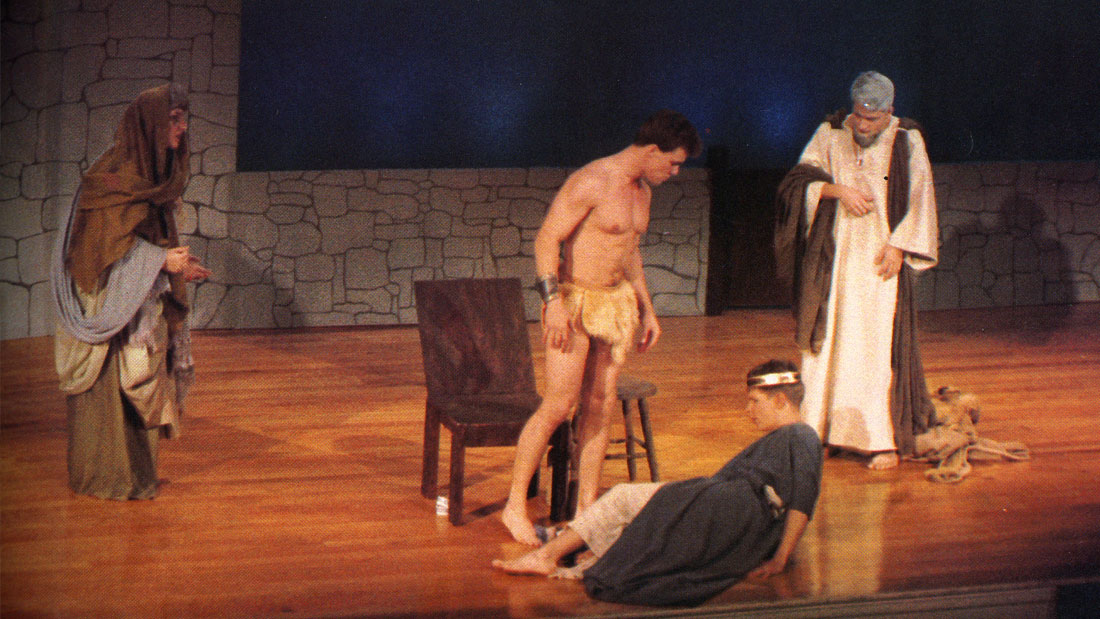

The story of Alcestis has been retold many times. When her husband Admetus, King of Thessaly, was mortally ill, someone volunteered to die in his stead. Alcestis assumes the sacrifice and dies. The mighty Hercules happened to arrive at the palace during the funeral; he descended into the underworld, strove with Death, and brought her back to life. The second act of my play retells this story. There is, however, another legend involving King Admetus. Zeus, the father of gods and men, commanded Apollo to descend to earth and to live for one year as a man among men. Apollo chose to live as a herdsman in the fields of King Admetus. The story serves as the basis of my first act. My third act makes free use of the tradition that Admetus and Alcestis in their old age were supplanted by a tyrant and lived on as slaves in the palace where they had once been the rulers.

On one level, my play recounts the life of a woman–of many women–from bewildered bride to sorely tested wife to overburdened old age. On another level it is a wildly romantic story of gods and men, of death and hell and resurrection, of great loves and great trials, of usurpation and revenge. On another level, however, it is a comedy about a very serious matter.

These legends seem at first glance to be clear enough. One would say that they had been retold for our edification; they are exemplary. Yet on closer view many of them–the stories of Oedipus, of the sacrifice of Isaac, of Cassandra–give the impression of having been retained down the ages because they are ambiguous and puzzling. We are told that Apollo loved Admetus and Alcestis. If so, how strangely he exhibited it. It must make for considerable discomfort to have the god of the sun, of healing and song, housed among one’s farm workers. And why should divine love impose on a devoted couple the decision as to which should die for the other? And why (though the question has been asked so many millions of times) should the omnipotent friend permit some noble human beings to end their days in humiliation and suffering?

Following some meditations of Soren Kierkegaard, I have written a comedy about the extreme difficulty of any dialogue between heaven and earth, about the misunderstandings that result from the ‘incommensurability of things human and divine.’ Kierkegaard described God under the image of ‘the unhappy lover.’ If He revealed Himself to us in His glory, we would fall down in abasement, but abasement is not love. If He divested Himself of the divine attributes in order to come nearer to us, that would be an act of condescension. This is a play about how Apollo searched for a language in which he could converse with Admetus and Alcestis and with their innumerable descendants; and about how Alcestis, through many a blunder, learned how to listen and interpret the things that Apollo was so urgently trying to say to her.

Yet I am aware of other levels, and perhaps deeper ones that will only become apparent to me later.

LICENSING

Amateur Productions in the USA, Puerto Rico and Commonwealth Countries:

Samuel French Inc.

All Professional Productions; Amateur Productions outside the USA and Commonwealth Countries:

Alan Brodie Representation Ltd.

PURCHASE

Thornton Wilder: Collected Plays and Writings on Theater, published by the Library of America