Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder as "An Endangered Species"

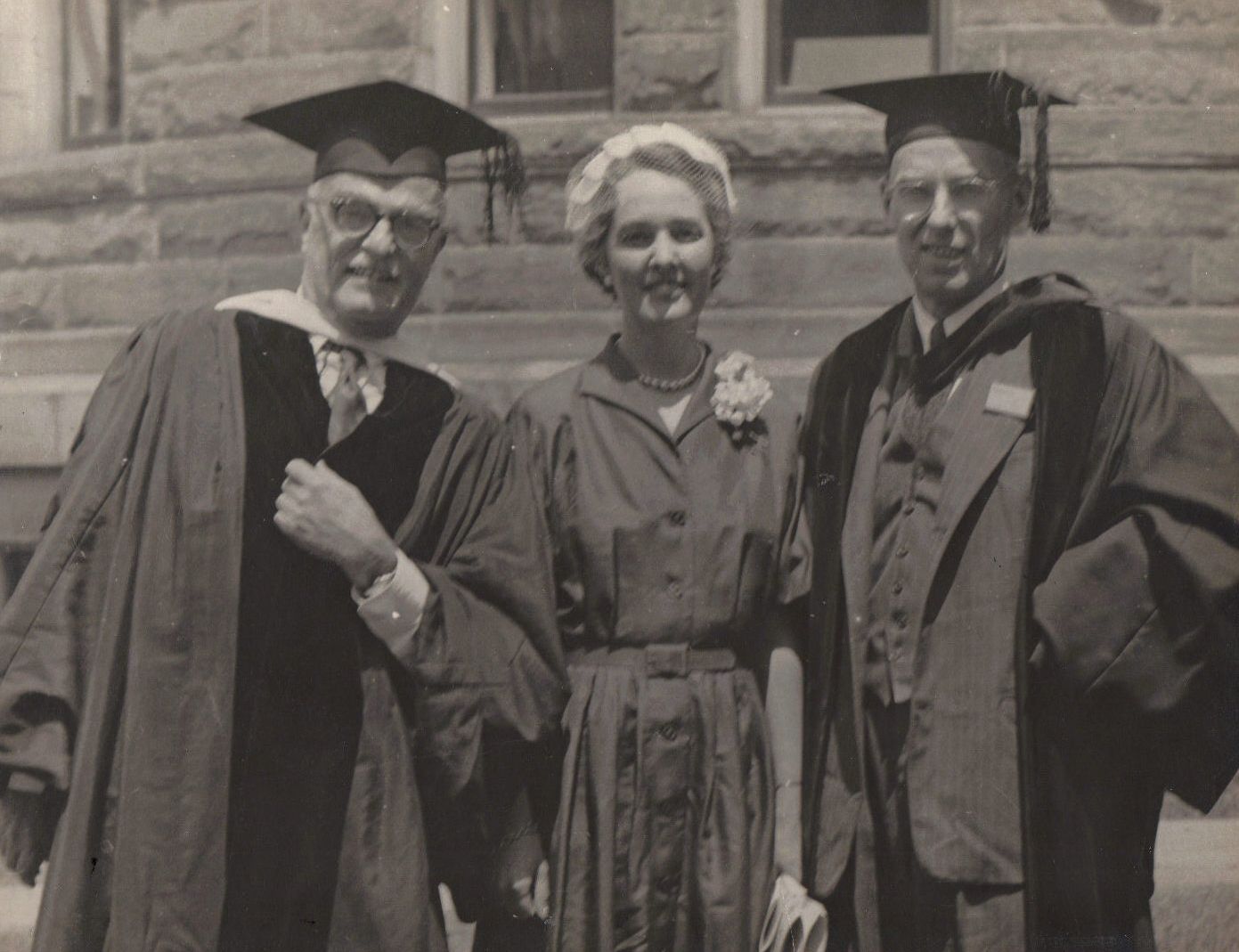

Catharine Kerlin Wilder (1906-2006) published a book of memoirs in 2000 entitled Milestones in My Life . In this essay, entitled Endangered Species, she paints an extraordinary portrait of her mother-in-law, Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder. Pictured here is Catharine Wilder with her brother-in-law Thornton (left) and husband Amos at Oberlin College in 1952 when both brothers received honorary degrees.

This past fall I began going through family letters that needed to be sorted in preparation for their being placed in the Beinecke Library at Yale University. At the time I noticed an article on the Op Ed page of The New York Times, entitled "Latin, and Other Lessons." The author wrote that his teacher, to give a splendid example of the dative-of-reference, had taught his pupil to say, in Latin, "Despair of all hope while your mother-in-law is alive."

When I encountered this devastating example of abuse, both of the pupil and of the mother-in-law, my Saturday Morning Club paper suddenly took shape in my mind. I would cite my own mother-in-law, Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder, as an example of an endangered species just because she was a rare human being, could not be stereotyped, and had qualities of character that are fast becoming extinct among the species of females today.

Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder circa 1932

She came into my life in the fall of 1934, and from the time of my marriage to her older son, Amos Niven Wilder, in June 1935, we carried on a correspondence. It had been my habit to write a weekly letter to my parents, a habit begun when I was in boarding school, so I decided to continue this same practice with my new in-law. I had been away from my own home for twelve years before I married, and during this time I had grown to appreciate the role a letter, no matter how long or how short, could play in continuing the family relationship on an adult level.

Isabella Thornton Niven was a daughter of a Scotch Presbyterian minister, whose parish for forty-three years had been located in Dobbs Ferry on the Hudson. She attended Miss Master's School from kindergarten through graduation, and at twenty-one, in December 1894, married Amos Parker Wilder, who was eleven years her senior. He had been graduated from Yale University and received his Ph.D. there.

The bridal couple moved to Madison, Wisconsin, where Father Wilder had purchased a newspaper, The Wisconsin State Journal. He was interested in the Progressive movement in that state, and wanted to use his editorial-writing ability, as well as his talent as a public speaker, to further this political trend in that state.

Mother Wilder had her first four children as fast as nature would permit. All were born at home. Thornton, the second, was a twin; his twin brother was stillborn. Two girls, Charlotte and Isabel, came next. When my husband, the eldest, was eleven, the family moved to China, where Father

Wilder became U.S. consul general in Hong Kong. His friendship with William Howard Taft, then secretary of war, and his disillusionment with the La Follette movement, led to this family upheaval in 1906.

Life in Hong Kong proved not to be what the Wilder parents wanted for their children. So Mother Wilder returned to Berkeley, California, after six months, with the four children, and rented a house there, where the schools and the community life were to her liking. Father Wilder remained in China but did make trips "home" to see his family. A fifth child, Janet, was born in 1910. The nurse who had assisted in the previous births was summoned from Madison.

Isabel, Thornton, Isabella, and Charlotte with little sister Janet. Berkeley, California 1914 or 1915

Six weeks after the birth, the mother, baby, nurse, and three children returned to China, where Father Wilder had been transferred to Shanghai. Amos was left at the Thacher School in Ojai to prepare for college. Six months later Mother Wilder, the baby, the nurse, and one child, Isabel, moved on to Florence, Italy, to be with her mother and sister, leaving Thornton and Charlotte in the British Chefoo School. Father Wilder remained in Shanghai.

This is a brief introduction to the woman who was still to have more travels, and later the burden of caring for a husband whose robust health was broken by an Eastern disease called spru, which at that time defied any cure.

“The House That Bridge Built” Deepwood Drive, Hamden Connecticut

When I came into Isabella's life she was living in Hamden, Connecticut, just over the New Haven line, in a home called "The House the Bridge Built." Thornton used the first royalties from his best seller, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, to provide his mother with a dream house in the woods on a cliff overlooking New Haven. The house was built in 1929-1930.

Isabella's letters to me were never more than four pages long. She worried about the time I was taking out of my busy life to write, so early in our exchange she warned me, “I’d always rather have a short letter or a postcard often than a long letter less often:' She was an underliner, and she was definite in her likes and dislikes. As I reread her letters, I was struck by the range of her interests as well as her vigor.

Our correspondence not only revealed her life, but records the comings and goings of her unmarried children. Isabel lived at home during this period to help Mother Wilder with Father Wilder's care and the abundance of mail that poured in after the publication of The Bridge of San Luis Rey.

Mother Wilder was always interested in theater. She watched for train-fare reductions that would enable her to get to New York or Boston to see shows. She had gone through a difficult financial retrenchment in the family when her husband became ill in China and had to give up his China post just when five children were entering college careers; so she economized whenever she could, and squeezed in a good show whenever possible. In 1939 she wrote: "I just caught the three o'clock train [for New York] by running the long platform. The coaches were half a mile down near the engine."

Later in 1939 the following arrived:

Would you post me a card the minute (or soon!) after you get this to say whether you and Amos have yet been to see Key Largo by Maxwell Anderson now at the Colonial Theater in Boston. I just discovered it in the N.Y. Sunday paper. I am keen to see it on Sat. and could go from South Station to the matinee. If you people have not seen it already last week, I should like you to be my guests at it.

Of course, she never missed a dramatic opportunity in New Haven, such as the following one:

Today I am having a treat-going to see Maurice Evans in his long Hamlet here for three nights and one matinee … Mr. Phelps induced Maurice Evans to give a Bergen lecture on 'acting Shakespeare' on Mon. afternoon. They opened Woolsey Hall for it and that huge place was filled. Evans' voice was perfect in it and one could hardly hear Billy Phelps. That shows what English stage training does for the voice.

Naturally, she was very excited and interested in Thornton's move into the theatrical world. Memorable evenings took place in the Wilder living room when Thornton read acts of his plays to intimate friends and received their reactions to his new approach to dramatic writing. His mother was one of his best critics. In January 1942, she wrote:

T went off on Mon. by train to Phila. to hide away in Benjamin Franklin hotel. He suddenly got light on the second act [of Skin of Our Teeth] which everyone tells him is too hard on the human race. Nobody loves a Jeremiah and he apparently wants to be loved more than to tell the truth about the whole race of anthropoid worms.

Our Town opened in Boston in January 1938. It failed in the first week, but was saved by Mark Connolly, who was summoned from New York to pass judgment on it. After the first act he said, "Take this play right out of Boston to Broadway." Jed Harris was the producer, and there were tense moments between him and Thornton before the play opened, and when it became a hit, Jed Harris grew to be more of a trial. Mother Wilder followed every stage of this difficulty between Thornton and his first theatrical producer. In February, 1939, she wrote:

There is a scandal about the closing of the tour [Our Town]. It is Jed Harris. Between drink, drugs, and thwarted ambition to make oceans of money, he has deliberately canceled the tour, though big audiences everywhere and theatres booked in a doz. cities … We already have a telegram from Los Angeles, where the film actor, Horton, wants to buy out Jed Harris and take the play up and down the west coast. It is too long a story but full of "skull duggery" on Jed's part.

Mother Wilder belonged to a reading group In New Haven, as well as one similar to ours where papers were written. After one of the meetings, she wrote:

I’ve been to read at Mrs. Baker's with the group … We've just finished Victoria Regina by Housman and next time we begin the Yale Press "best seller" as Gene [Davidson, head of Press] calls it, Sweden and the Middle Course. Gene gave me a copy. I had Santayana [Last Puritan] from the library and could not lay it down. Very poor characterization, but it does not matter. What ripe and not completely cynical wisdom! Perhaps old people who are dissatisfied with the world will better appreciate those of us who have seen the world.

Isabella's criticisms at these events were greatly valued and they spilled over into her letters. Of Dorothy Thompson, she recorded:

Thornton was immensely impressed by the enclosed book review by Dorothy Thompson. T and I both think she often gets very emotional and therefore feminine in some of her speeches and columns but we think this is her most reasoned and intelligent best. Nobody can phrase things better than she, when she is at her best.

Of course she followed all the outstanding public lectures at Yale. The riches of a university city were her lifeblood, and in Madison, Berkeley, Oxford, Paris, London, Florence, and New Haven she was in her element. Her spark, wit, and perceptiveness were appreciated by numerous friends and acquaintances. Her knowledge of French and Italian enlarged her horizons at home and abroad. In January 1943, she recorded:

I have been to no. 1 of Jacques Maritain's "Terry" lectures and I shall go to fourth and last tomorrow. They are an education, the first very nebulous--as though every youth in high school and academic college had a philosophical mind and equipment. These fine-lined people do not know how exceptional they are. As tho one could legislate technical and scientific specialization out of all schools! That would leave 90% of students stranded like fish out of water. Why, fifty percent of humanity is not even perceptive of ordinary moral concepts (ethical) & scarcely any of spiritual!! I was a bit impatient and even bored--so repetitious.

Whenever possible Isabella was present at her children's performances. Of course, she was proud of every one of them, but she refrained from expressing this. She took it for granted and saw room for greater improvement. After one of Thornton's lectures, she wrote:

Thornton's Yale lecture yesterday went very well-a crowded hall, people (overflow) seated on platform. If T would only write out his lectures they would be supreme in their class. The material is so good. The subject was "The Myth and the Novel", based on Aristotle's definition of the narrative form.

Her interests were not solely literary, but included the current events of her time. She read the the New York Times very carefully, listened to her favorite radio commentators, and attended lectures on political, social, and economic subjects in New Haven, as she had had in other university communities. In March 1945, she noted:

The last c. event of our season here comes tomorrow. It is to be on Britain and our relations with same. I hope she (Miss Avery) does not take the India for India stand. Order and security so essential now for the next few years, east and west, that all the powers ought to hang onto the white man's burden a few short decades more-even we in Philippines. They don't want us to leave them now. A ceiling of B- 29's and a fleet of destroyers looks good to them and should look good to Burma, India, Java, etc. not to mention Siam and French Indochina! Even China will like us to stay a while. They could all be so much worse under any Asiatic domination and they should know there are no Utopias in the best Peace!

Each lecturer received her penetrating critical judgment, as did Professor Walton Hamilton in 1945. After his lecture on "Whose International Economy?" Isabella wrote:

This prof. of Yale Law School is loaned to Washington as assistant counsel to Attorney Gen. He is brilliantly fluent but amusingly inadequate. You are entertained but not Jed-nothing constructive. Basically pessimistic as to mercantile operations in war & peace.

She followed the course of the League of Nations and attended luncheons and dinners given to arouse interest in this struggling organization.

Thornton Wilder’s mother, Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder, 1944, age seventy-one

In 1939 Amos was teaching at the Andover-Newton Theological School in Newton Center. The trustees there voted to build a faculty house for us when we needed more room for our growing family. There were many references to building in the letter that followed this decision. Mother Wilder had given great thought to her own home in the woods. She had much knowledge and advice to give to me, and she enjoyed driving up to Newton Center with Isabel, to follow the construction of the house. She wrote:

We love quarter-finished houses and are adept at crawling over open beams and up sketch ladderlike stairways.

After we acquired our Blue Hill, Maine, property in 1940, Mother Wilder was eager to interest me in the recent possibilities of modern architecture for our location:

I have an idea for your Maine cottage. Drive over to Belmont, the Snake Hill Colony. The architect has a dozen semi-modernistic, very large-windowed houses on a development there. I saw it at the Yale architecture department exhibit. A student had made a model of the whole hillside and separate models and drawings. You might find just what you need.

She was delighted to have grandchildren, but after raising five children of her own, she never wanted to be responsible for any care of the second generation. A visit of a few hours with them in our home was sufficient, and her own home did not have room or equipment for them. She had had her share of children, and she was careful never again to feel the burden of any more. She had no hesitation in writing her feelings in regard to this:

The difficulty of small children is the continual dayliness of them. Every day needing this constant care and watching. I don't think young women realize all that when they marry. I know I didn't .... Three meals will be three meals the rest of her baby and childhood- merely more varied diet as she gets older.

In fact, Mother Wilder thought of plans so that I, a young mother, could get a respite from responsibilities. In 1943 she suggested the following plan for Easter:

Isabel and I were wondering if you could install a practical nurse who would cook and care for the two infants and give you two the chance of a visit away from them. It would do you good. We could not put up so many and besides it is best for children to be in their own place and very good for the elders to be away from them. All the years I was in Madison· I hired in a nurse and went East alone and saved a break-down usually. That was a two or three week outing.

Although Mother Wilder was intellectual in her interests, she could be mundane too and from time to time she sent me information on food:

I sent a little canning book not because I thought you needed it but because there is a recipe for tomato preserves and marmalade which I am putting up. My mother used to make it and I always loved it.

I am sure she questioned my cooking ability when I first married. Also, she gave me clues about what she would do were Amos ill and in her care:

Remind Amos to take some sulphate of quinine (agrs. pill) twice a day for a few days-nothing so bracing. It is only the tonic bark of a tree but miraculous in effect. I warded off flu and liverish symptoms with it lately.

While listening to her favorite radio programs, especially classical music, she darned, knitted, and sewed. Her hands were never idle.

I cannot recall Mother Wilder going to a doctor or complaining of any dental problems. She had her own home cures. During 1946, her letters showed that she was winding down. She always enjoyed having her family around her, but she noted how fatigued she became from their presence:

I enjoyed visit with Amos immensely, ill as I was; he was like a remedy. But then I got tired again with the chattiness of our later guest (Aunt C does love talk) and Thornton, a joy to have made my excitement a bit beyond sick strength.

Also in 1946, she wrote:

With Thornton here, time passes fast and I don't sit down to write much. Seems like this is a constantly dirty house full of dust, cigarette ashes and crumbs. I am not as spry as I used to be. I don't go about nearly as much and take naps more. I take twice as long to do my chores so am become a homebody for the first time since my children were small.

In July of that year Mother Wilder went to Nantucket for her vacation with Thornton and Isabel. Shortly after her arrival there, she was rushed to the hospital when she was stricken with a severe abdominal pain. Thornton sent a private plane to the Trenton airport on Mount Desert Island, to pick up Amos. Her end came with four of her children at her bedside.

Now you may understand why I consider my mother-in- law, Isabella Thornton Niven Wilder, an example of an endangered species